The Movement Action Plan

A tool to analyse the progression of your movement

This guide is also available in PDF format (in Dutch).

Activists often feel powerless, especially when their movement is doing well and is on the way to success. Understanding how a movement works and recognizing its success can fuel the power of groups and activists within a movement. The Movement Action Plan, developed in the 1980s by Bill Moyer, is a great tool for this. It outlines eight stages of successful movements and four roles that activists need to play.

Strategic assumptionsThe Movement Action Plan is based on seven assumptions:

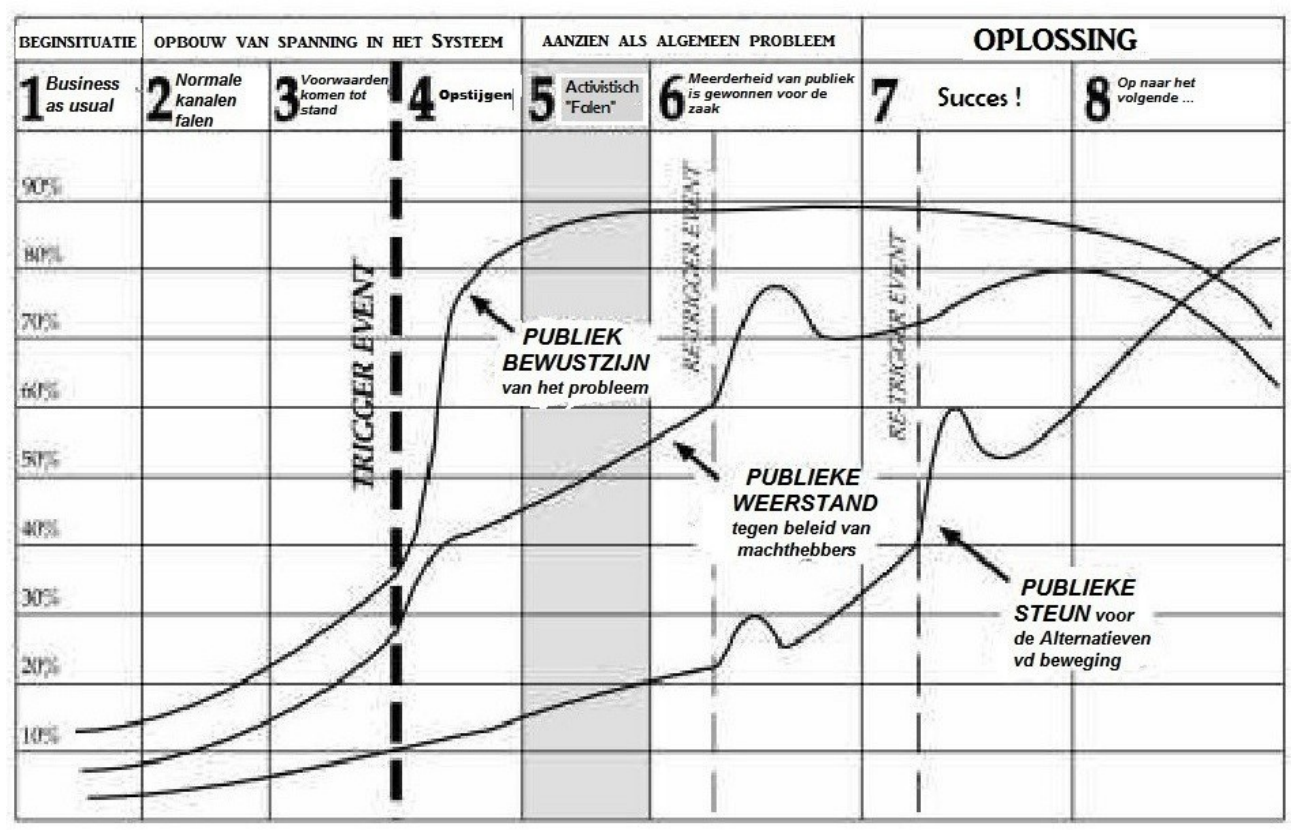

| Eight stages of social movementsA movement begins without being aware of it. In Stage 1, business as usual, the movement's primary goal is to make people think and show that there is a problem. The next step is to show that the usual channels fail (Stage 2). Through hearings, legal actions, participation in administrative procedures, etc., the movement demonstrates that these institutions and procedures will not act on behalf of the people to solve the problem: the people will have to act themselves. This leads to Stage 3: the conditions are ripe for the development of a social movement. People start listening and form new groups, small acts of civil disobedience bring the issue to the forefront. The powers that be get irritated, but continue as before. If the movement does its homework (organizing new groups, developing networks, building coalitions), it can "rise" (Stage 4) after a "trigger event" (the starting point). This could be an action by the movement itself: the occupation of a construction site in Wyhl, Germany, in 1974, was the starting point for the anti-nuclear movement. It could also be something done by the powers that be. The trigger event leads to mass demonstrations, wide campaigns of civil disobedience, and extensive media attention. Despite the large public sympathy for the movement, the powers that be usually do not give up at this stage. This often leads to a sense of failure among activists (Stage 5). This is reinforced by decreased participation in the movement’s events and negative attention in the media. However, in the meantime, the movement gains the majority of the population on its side (Stage 6). Up until now, the movement focused on protest. Now, it is important to offer solutions. About three-quarters of society now believes that change is needed. The powers that be will attempt to deceive the movement, increase repression, and employ tricks. The movement must try to stop these tricks and offer an alternative solution. True success (Stage 7) is a long-term process and often hard to recognize. The movement’s task is not only to have its demands granted but also to achieve a shift in paradigm, a new way of thinking. Closing all nuclear power plants without changing our vision of energy merely shifts the problem from radioactivity to CO2 (though the former is already an achievement in itself). If we only ensure a few more women in the executive committee, it still doesn't change the structure of our patriarchal society. After the movement has succeeded—either through confrontational struggle or long-term weakening of the powers that be—it must anchor this success. Anchoring the success and moving on to other struggles (Stage 8) is now the new task of the movement. |

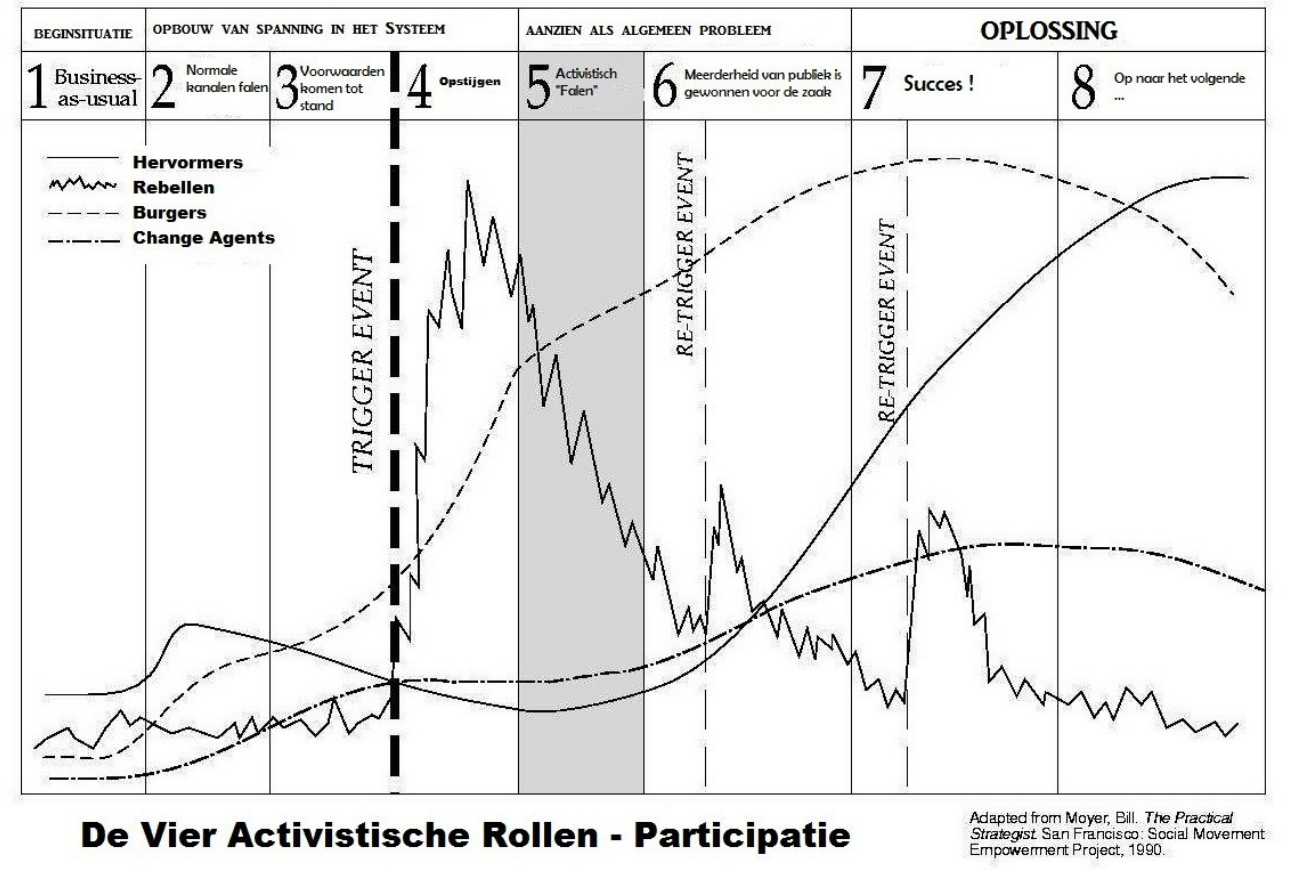

Four roles of activistsIn the eight stages, activists have different tasks. These tasks are not all carried out by the same type of activist. Generally, four types of activists can be identified. All four must be present and work together to make the movement succeed. The REBEL is the type of activist many associate with social movements. Through nonviolent direct actions and openly saying "no," rebels put the issue on the political agenda. However, they may hurt the cause by positioning themselves as the lone voice on the fringe of society and by adopting a radical militant stance. Rebels are important in stages 3 and 4 and after each Trigger Event, but they often shift to other developing movements in stage 6 or later. REFORMERS (lobbyists) are sometimes viewed skeptically in movements, but they are the ones who highlight the failures of existing channels or promote alternative solutions. However, they often overestimate the value of institutions and suggest reforms that are too narrow to truly secure the movement’s success. CITIZENS ensure the movement maintains contact with its target audience. They show that the movement is rooted in society (e.g., three teachers, scientists, and farmers protesting nuclear waste transport in Gorleben) and protect it from repression. They can be ineffective if they still believe the claim of the authorities that they serve the public interest. The ORGANIZER (change agent) is key in any movement. Organizers handle education, persuade the majority of society, organize grassroots networks, and support long-term strategies. They too can be ineffective if they cling to utopian visions or promote only one "right" approach. They may also ignore the personal concerns of activists. | What now?Social movements are complex. They don’t follow the Movement Action Plan like a map. But understanding the stage of your movement and the activists involved can help you recognize successes and plan for the future. If you're lost, check this Plan!  Source: Silke Kreusel & Andreas Speck (published in Peace News, No 2423, March 1998), based on Bill Moyer, The Movement Action Plan: A Strategic Framework Describing The Eight Stages of Successful Social Movements (1987). |

Finally

Interested in attending a training? Contact us here.

This guide is part of the ‘Toolbox for Movements’. This toolbox contains more short digital guides, offering fundamental knowledge about strategy, movement building, campaigning, and organizing.

We also love to learn. So, if you have any ideas for improving or adding to this guide based on your experiences, let us know!